4. Keynesian Business Cycles and Policy¶

We begin with the orthodoxy in macroeconomic textbooks and in most central-bank policy thinking: Keynesianism. The goal here is to ensure that we all understand and master the methods and insights from this school of thought, before we begin wondering about alternatives.

Like a good mix tape, we’ll start with some easy tracks and then we’ll ramp it up. Finally, we tear it all down with some critical (and open) questions. There are still new riffs to be played …

4.1. Cartoon theorizing¶

We first re-visit a version of the textbook Keynesian model geometrically. The following slides based on material found in an intermediate textbook like [Mi2015] or [Jo2014] will help set the stage in terms of developing intuition and basic lessons.

4.2. Learning the nuts and bolts¶

Once we’ve got these bad boys nailed down, we’ll start developing slightly more R-rated (R for “rigorous”) versions of these ideas using some mathematical and computational tools. We’ll do so in our TutoLabo sessions.

Note

Why the mathematical discipline? Think/Discuss.

- How would you take your IS-MP-PC ideas to the data directly?

- The intermediate textbook versions of IS-MP-PC give you qualitative predictions. How would you attempt to deduce any quantitative results from it?

- Dani Rodrik: “[W]e use math not because we are smart, but because we are not smart enough”.

“

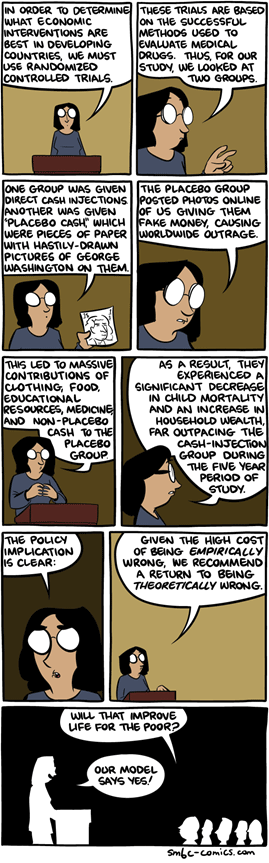

4.3. Caveat emptor¶

Recall how we mentioned that Macroeconomics is a difficult subject? We ask big questions, so we set ourselves up for a big fall too. No matter how precise we get in our modelling exercises as economists, our models are very likely to be inaccurate when confronted with reality:

Indeed, the textbook Keynesian IS-PC-MP logical paradigm for macroeconomic policy thinking may have some flaws—both in its internal logic and also in terms of its external validity (with respect to observational data). In the following set of slides, we’ll first attack the question of observed data and the Keynesian theory’s external consistency. Then we’ll study a simplified version of the famous Lucas Phillips curve model and show that the so-called Phillips curve correlation may not be a stable one, as seen in some recent data.

The mantra of the week here is

“In macro data and policy, WYSMNBWYG”.

(WYSMNBWYG stands for “What You See May Not Be What You Get”.) Lucas’ lesson from 1972 warns us about modelling economic behavior as fixed statistical correlation models. To paraphrase the Greek story from Virgil’s Aeneid or Homer’s Odyssey, one should beware of (some behavioral) economic modellers bearing free parameters (i.e., a model whose assumption—as opposed to result—is “too close” to the observed statistical behavior to be modelled.)

Slides on recent "Phillips curve" dataNotes on Williamson's article- [Lu1972]

Lessons from 1972 - Steve Williamson’s critique

| [Jo2014] | Jones, C. (2014). Macroeconomics, 3rd edition, Norton. http://library.anu.edu.au/record=b2879421 |

| [Lu1972] | Lucas, R. (1972). Expectations and the neutrality of money, Journal of Economic Theory, 4(2), 103-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-0531(72)90142-1 |

| [Mi2015] | Mishkin, F. (2015). Macroeconomics: Policy and Practice, 2nd edition, Pearson. http://library.anu.edu.au/record=b3578493 |